Authored by:

Robert Koenigsberger, Managing Partner & Chief Investment Officer

Mohamed El-Erian, Senior Advisor

Kathryn Exum, Senior Vice President & Co-Head of Sovereign Research

Petar Atanasov, Senior Vice President & Co-Head of Sovereign Research

April 13, 2020

We enter the second quarter in uncharted territory and hopeful for a bright spot on the horizon. A thoughtful approach to the current environment coupled with a deliberate plan going forward should serve investors well in their pursuit of portfolio returns. In this paper, our investment team explores several themes we believe are most relevant in evaluating investment options and we summarize how we expect to best take advantage of the opportunity set and manage the risks.

A Top-down Perspective and Related Implications for Emerging Markets

The global economy and markets enter the second quarter of 2020 in an extraordinarily unsettled and uncertain state. Most normal economic activity is shut down in the majority of countries around the world. International trade has plunged. Governments and central banks have intervened in unprecedented fashion, both in scale and in scope. And there remains a big question about when and how the global economic restart will proceed.

The cause of all this is, of course, the coronavirus, whose destruction of human lives and economic well-being seems to know no national or global boundaries as yet. Unable to effectively contain its spread, government after government has resorted to policies of social distancing, separation and isolation. Pending durable medical solutions, the hope is to “flatten the curve” to avoid healthcare systems being overwhelmed and paralyzed. But this understandable health priority has severe economic and financial costs, especially for a global economy whose initial conditions included years of sluggish growth and productivity, excessive reliance on central bank policies, insufficient appreciation of liquidity risks, and, with that, asset prices decoupled from underlying corporate and economic fundamentals (see our 1Q Outlook).

As bad as all this sounds, the situation would have been even worse were it not for the dramatic policy interventions in the second half of March.

Guided by an “all in,” “whatever-it-takes,” and “whole of government approach,” a series of exceptional measures were deployed around the world to contain the economic and financial damage, and to avert crippling market failures. The result has been to avoid for now that awful combination of a 1930s-like depression and 2008-like global financial crisis. But neither a global recession nor a quick restart is in the hands of economic and financial policies. That depends on medical advances in identifying and containing the spread of the virus, better treating illness and increasing immunity.

As to what this means for second quarter key global variables that influence investment outcomes, look for an unprecedented decline in growth, employment, income, productivity, trade and most commodity prices. Most balance sheets, corporate and domestic, will be stressed. Some will navigate this well, some will succumb to bankruptcy and others will obtain government support on yet unspecified terms.

The rebound, when it comes (probably beyond the quarter), will be significant but uneven given the sequential nature of a global economic restart, especially from a “sudden stop.” Together with how we navigate the journey to this more optimistic destination, the way we collectively handle the recovery will also be part of this generation defining moment. Much will depend on the ability to synchronize and coordinate different sectors, as well as the ability to understand and operate in what will be a different post-crisis landscape.

Themes Influencing Investment Decisions in the Second Quarter.

Theme 1: The unprecedented and unpredictable global health crisis triggered by the COVID-19 virus will almost certainly push the previously fragile global economy into a sudden and deep recession. The expected timing and degree of recovery will be a key driver for markets as we head into the second quarter. The duration and severity of the recession will depend on the effectiveness of global containment measures and prospects for health solutions while the robustness of recovery will be linked to the scope and nature of the policy response and the amount of damage already incurred by businesses and households.

The exponential spread of the coronavirus pandemic and associated containment efforts continue to cause a series of domestic and external economic shocks linked to both supply and demand factors. As of the morning of April 13, confirmed cases globally approach 2 million compared to roughly 85k at the start of March, but in all likelihood are considerably higher given still very limited testing capabilities in most countries. New daily cases over the past few days have increased beyond 80k compared to under 5k of new cases per day throughout most of February. Please see the information compiled by Johns Hopkins in their COVID-19 Case Tracker.

Containment measures including travel restrictions, school and business closures, and remote work combined with the psychological effect of the crisis have caused supply and demand to drop precipitously first in China (February composite PMI of 27.5) and now in Europe, the U.S. and a growing part of the developing world. The Chinese Government’s strict quarantine efforts appear to have stabilized cases in the country for the time being and high frequency data for March suggest that there is a gradual pick-up in activity, although still well below 2019 levels and comfortably in contractionary territory on an annualized basis. We anticipate similar shocks to Europe and U.S. March data through the end of 1Q into 2Q and potentially beyond.

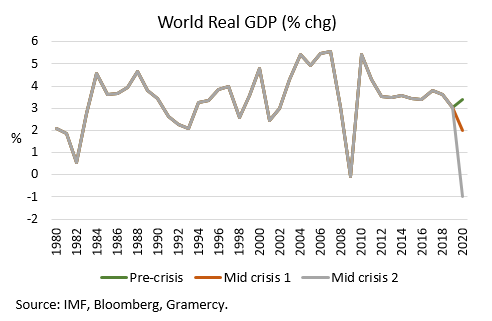

Downward revisions to 2020 global growth have been ongoing since the start of the outbreak in China. The average street forecast was initially around 2% YoY, but is in the process of being scaled down further with the latest consensus likely to settle somewhere between -1% and zero growth for the year. In their World Economic Outlook update in April, the IMF should materially lower its forecast from the 3.3% YoY level set in January. We anticipate global growth to be on the lower end of this new range, assuming the crisis persists and deepens in the U.S. and Europe through most of 2Q (Exhibit 1). This is slightly worse than the Global Financial Crisis contraction but given the magnitude of the drop in China, a more constrained policy response by Chinese authorities relative to 2009 given concerns over financial imbalances, and prevailing uncertainty, we think this more pessimistic forecast is warranted.

Exhibit 1: Global growth shock could rival that of the global financial crisis.

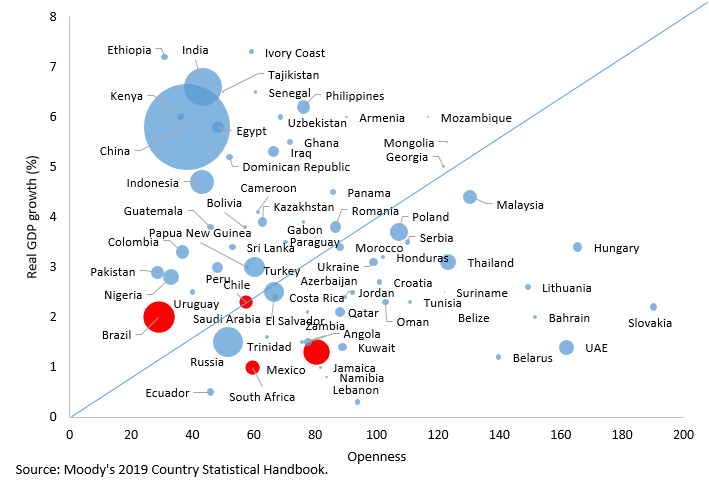

Growth in emerging markets will decline meaningfully, but the severity and recovery in any given country will likely vary dependent upon the domestic spread, economic and financial management of the crisis, overall vulnerability to external demand, access to financing and pre-existing fragilities. Of the larger emerging economies, Mexico, South Africa, Chile and Brazil are a few major EM economies that remain particularly exposed to the global economic activity fallout, including due to also being commodity exporters (Exhibit 2).

Exhibit 2: Open economies with already low growth are most vulnerable to COVID-19 shock.

In all cases, the economies were already facing domestic strain related to political factors and fragile growth conditions. Mexico’s limited response thus far to contain or address the virus outbreak in conjunction with its proximity to the U.S. indicate that the economic impact will be sizeable and potentially prolonged given persistent policy uncertainty and a likely increasingly unorthodox approach. South Africa’s already high unemployment rate, weak growth, and fiscal challenges leave it in an inadequate position to cope with the shock. Chile’s lack of diversification and social pressures will exacerbate the impact. However, its comparatively robust fiscal space provides the government with greater ability to restore growth as the situation normalizes relative to others.

Brazil is on the other end of the spectrum relative to Chile in terms of fiscal space: the government in Latin America’s largest economy faces severe fiscal constraints given its weak starting position characterized by high sovereign debt burden and budget deficit and structurally elevated government expenditures as share of GDP. As such, Brazil’s authorities will face significant limitations in the scope of economic stimulus they can provide to an already sluggish economy ahead of the crisis.

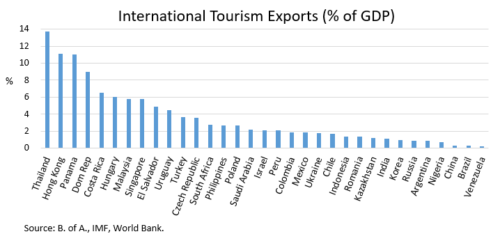

The collapse in tourism will also weigh on growth in economies more heavily reliant on the industry. Thailand, Hong Kong, Panama, Dominican Republic and Costa Rica are among the countries with the highest tourism receipts relative to GDP. While South Africa’s exposure to the sector is a bit lower, the country’s other vulnerabilities will likely amplify this shock (Exhibit 3).

Exhibit 3: Tourism is a significant growth and liquidity driver in select economies.

The capitulation in oil markets that took place during March as a result of the price war between Saudi Arabia and Russia as well as realization of substantially weaker global demand has caused significant underperformance in several EM oil credits. The end of the price war (or at least ceasefire) that was reached on April 12th will likely stabilize oil prices at a low level, but will be insufficient to spearhead a material recovery until the significant extra supply accumulated over the last few weeks has been cleared from the market. From a sovereign credit risk perspective, the most vulnerable sovereigns are those with a high degree of reliance on oil exports and oil for fiscal revenue combined with high fiscal and external break-even prices and limited buffers (e.g. Oman, Angola, Iraq etc.). The duration of the price shock, the country’s respective reserve buffer as well as its multilateral relationships will be key determinants of their ability to weather the price rout and prospects for recovery. Several credits in the EM universe (e.g. Ukraine, Lebanon, Jamaica, Pakistan, etc.) benefit from lower oil prices as net importers of the commodity, many of which also provide subsidies to their populations lowering fiscal as well as external costs.

We anticipate an eventual robust global recovery on the back of pent up demand and sizeable policy support but the timing and immediate rebound remains relatively uncertain given medical constraints and still many unknowns about the virus itself. The unprecedented disruption to the system makes it difficult to forecast and there will likely be a few differences in the post crisis world. We assign the highest probability to a U shaped recovery albeit likely with a more drawn out trough than consensus. While the rebound in global growth should shore-up EM as a whole, there will likely continue to be a notable differentiation across credits within the asset class given idiosyncratic challenges and political implications.

Theme 2: Massive policy response will likely have limited effectiveness on the real economy until the pandemic is under control; coordination of fiscal and monetary policy tools and scope to determine the robustness of recovery when the health crisis is over.

We expect one of the main paradigm shifts in global economic policy in the post-pandemic environment to be the “passing of the baton” by the monetary to fiscal authorities, at last. However, the global central banks were once again the “first responders” to the economic and financial emergency created by the huge exogenous shock due to the pandemic. Both Developed (DM) and Emerging Markets (EM) central banks have acted decisively with a mix of large rate cuts and liquidity infusions to alleviate pressures for struggling markets and economic agents. Furthermore, they have pretty much universally committed to “whatever it takes” measures to buffer the economic and financial fallout from the crisis.

The large systemic central banks (U.S. Federal Reserve, European Central Bank, Bank of England, and Bank of Japan) have announced trillions in asset purchases (QE) for as long as necessary to complement rate cuts and other liquidity measures such as swap lines to an increasing number of central banks globally in order to facilitate the provision of FX liquidity. This being said, measures from the monetary policy toolboxes of central banks that have been used consistently by global policymakers since the Global Financial Crisis in 2008-09 can yet again provide a backstop for freefalling markets, but are unlikely to be sufficient to jumpstart the global economy and provide sustained relief. In our view, this is where we see the key role for fiscal policy, but naturally fiscal measures take more time to materialize and are subject to the vagaries of domestic political realities, even in times of a great global emergency.

As the fiscal response is in the process of taking center stage, the numbers being discussed by policymakers and market participants are extraordinary and staggering. But so are the challenges that lay ahead in terms of reversing the unprecedented “sudden stop” in the global economy and revival of economic infrastructure, supply chains, industries etc. ravaged by the deadly virus pandemic.

Initial estimates about fiscal support to the U.S. economy by Congress is in the $2-4 trillion range, but the numbers could grow depending on the actual economic fallout over the coming months. So far the measures include direct cash transfers to most U.S. households as well as various lifelines for a number of industries affected by the economic impact of the pandemic.

In Europe, although some member states show resistance to the mutualization of fiscal costs via issuing so called “corona bonds” at the Euro Area level, the fiscal response has been robust and well-coordinated at the country level. According to the Euro group’s president Mario Centeno, Euro Area governments have on average adopted fiscal stimulus measures of around 2% of GDP and loan guarantees (to provide liquidity) of around 13% of GDP. In addition, the so called “escape clause” from the Euro Area fiscal rules has been activated, allowing national authorities to exceed the 3% deficit limit without triggering an excessive deficit procedure.

As for China, we believe that the government will also continue to introduce stimulus, but only gradually. Some portion of the Chinese stimulus will go to supporting the corporate and household sectors while the rest will be deployed on public spending projects in infrastructure, public health, and technology among other sectors.

We briefly summarize the extent of current fiscal measures being taken/proposed (we include measures widely expected to be adopted in the U.S. and Germany even if not officially legislated yet) by the G7 global economies and China vs the fiscal effort by the same economies in 2008-09 during the GFC (Exhibit 4).

Exhibit 4: Fiscal Tracker.

Assuming the expected fiscal packages in the U.S. and Germany emerge relatively undiluted from the legislation process, the COVID-19 fiscal stimulus by the G7 economies has already surpassed the measures by the same group in 2008-09 (~6% of G7 GDP now vs ~5% during the GFC) and will be increasing even further. For all intents and purposes, the effort by global policymakers is extraordinarily large. However, we note that the disruptions that the global economy is facing due to the coronavirus pandemic are truly unprecedented in modern times and we do not foresee a material improvement in market and economic sentiment until a sustainable resolution to the health crisis appears on the horizon, which is unlikely in the near future.

Furthermore, a possible second wave by the pandemic in late 2020 could further add to economic uncertainty and might require even more forceful policy action down the road. Once the world is sustainably beyond the pandemic (i.e. a vaccine is commercially available), the massive amounts of monetary and fiscal stimulus that are being pumped into the global economy will likely drive a robust recovery from a low base.

As global financing conditions deteriorated abruptly due to the acute market stress, many EM economies are facing dramatically higher borrowing costs and in some cases a sudden liquidity squeeze, despite massive amounts of liquidity being deployed by the systemically important central banks. In this unusual context, multilateral organizations such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank (WB) have augmented their rapidly-disbursing emergency assistance as well as more traditional funding facilities. For example, the IMF has made $50bn available under its Rapid Financing Instrument and Rapid Credit Facility to provide liquidity relief to EMs highly affected by the crisis. These facilities do not entail conditionality beyond being in good standing with the IMF (i.e. no arrears, IMF Article IV assessments etc.) and the size of the arrangements are typically 50-100% of respective quotas, depending on the country’s circumstance. Over 80 countries have reportedly asked the IMF for funds under this facility, including Ecuador, Ghana, Ukraine, Iran, and Venezuela and we anticipate more to come forward with requests in the coming days and weeks. The speedy nature of the financing absent policy criteria is positive for immediate near term balance of payment and liquidity pressures. However, it will be most beneficial for sovereigns with small short-term needs but it would not be sufficient to backstop those facing larger more structural liquidity challenges.

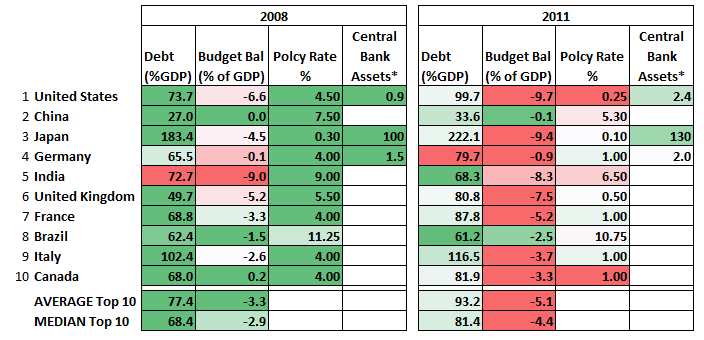

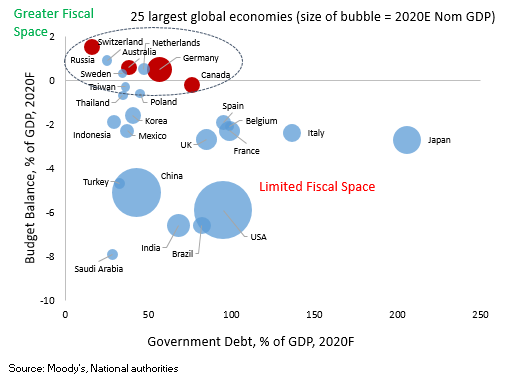

Finally in terms of economic policy response to the COVID-19 emergency, the global economy is entering this crisis with relatively limited policy space in relation to the most recent previous crisis episodes, especially on the monetary front. As shown in Exhibit 5 below, across the ten largest global economies, debt burdens have risen steadily since 2008 and almost all conventional monetary policy space has been used. While fiscal balances have generally improved vs. where they stood in 2011 (European debt crisis) and 2015 (China slowdown scare), all ten largest economies except Germany have relatively large fiscal deficits. Nevertheless, it is inevitable given the circumstances and the discussion on stimulus measures above that these budget deficits will grow even larger in the coming years, adding to already elevated debt burdens in the global economy. Furthermore, ever larger QE programs will increase the CB’s balance sheets to new heights, raising concerns about the eventual unwinding process at some point in the future and its effect on the global financial system.

Exhibit 5: Crisis Comparison: Now vs. Recent Events

Theme 3: The economic and investment world in the aftermath of the global health crisis will likely have a few key differences from the pre-shock paradigm. This could include a permanent partial erosion of the “buy the dip” mentality, higher debt and less fiscal space globally, deepened focus on resilience and protection of global supply chains which amplifies de-globalization efforts, a deeper entanglement of the state in the private sector and social and political implications which will likely shape future elections and policy.

The initial ineffectiveness of the policy response thus far, particularly from a monetary perspective, may leave investors less confident in the future backstop of excess liquidity even once conditions normalize. This would result in higher interest rates and greater credit differentiation than witnessed in the recent past.

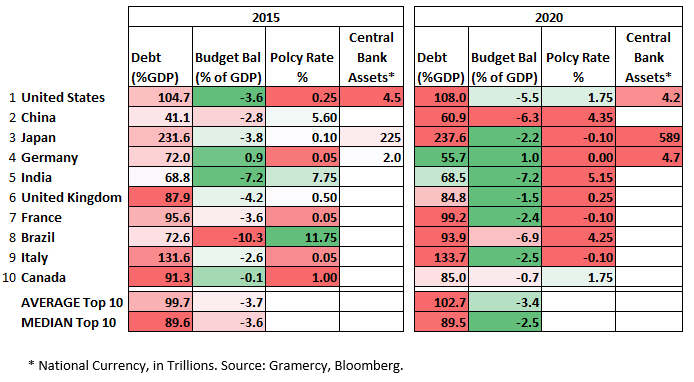

As fundamentals return as a core aspect of investment analysis, fiscal positions and the scope of stabilization and consolidation of the post-crisis response will come into focus, similar to the years following the GFC and Eurozone crisis. As governments implement fiscal stimulus on an even larger the scale compared to that deployed during the GFC, debt burdens will continue to rise at a steady pace globally and deficits will likely exceed peaks witnessed during this timeframe. Importantly, the initial fiscal impulse implemented in 2009 remained in place for multiple years before material consolidation began to occur. The ability for a sovereign to effectively manage this credit deterioration will be a function of its pre-crisis fiscal space as well as its political willingness and ability to catalyze improvement post-crisis and at what pace (Exhibit 6).

Exhibit 6: Fiscal Space is limited in many major economies.

The growing protectionist and nationalist trends witnessed over the past few years are likely to persist, particularly in the context of global supply chains and China, given the vulnerabilities further exposed by this crisis. While there may be evolution of the approach, particularly in the case of the U.S. to these issues under a Biden Presidency, we expect the pressure and trajectory towards China to stay the course.

This would include tough policy against Chinese technology companies, reduction in Chinese manufacturing hubs, potential financial measures and continued utilization of trade wars albeit to a lesser extent. There will be emerging market economies that benefit under this scenario, but others will face headwinds depending on political positions and economic comparative advantages.

Lastly, a government’s management and response to the crisis may affect the respective domestic political landscape and electoral outcomes over the medium term. In the case of the U.S., the depth of uncertainty and weakened sentiment has contributed to a significant outperformance and political comeback of Former Vice President Joe Biden in the Democratic primary. As the presumptive nominee, key questions ahead of the U.S. election will be President Trump’s ability to restore confidence and growth in time for the vote, the potential erosion of his support base or lack thereof as a result of early mishandling of the crisis, and risks to the election date itself, depending on the normalization of the health threat. If postponement comes into question, there will likely be volatility over the intent of the action and efforts by Democrats to push for an alternative means to vote and not dramatically alter the time frame.

In EM, the 2020 electoral impact is likely modest given a fairy light calendar for the duration of the year. There may be potential delay of the presidential elections in the Dominican Republic currently scheduled for May 17th but ultimately we envisage a more fiscally responsible government to emerge. Many of the electoral impacts will likely occur in 2021 with notable votes across Latin America including Ecuador (presidential), Mexico (mid-terms), Argentina (mid-terms), and Chile (presidential and legislative). Additionally, depending on the scope of spread in low-income economies, particularly in Africa, political volatility may surface regardless of formal elections.

On a similar note, many weak balance sheet economies and companies that face restructuring may begin to utilize this period, by force or choice, to reconsider debt obligations. While there will be liquidity continuously pumped into the system by governments, central banks, and multilaterals, it may be inadequate in some cases and politically unpalatable or less preferable in others. This period of uncertainty and potential inability to achieve resolution swiftly will likely result in select market dislocations and eventual high return opportunities across the emerging markets landscape.

Market Implications: The importance of strong balance sheets and resilient deal structures.

The multi-faceted nature of the worsening COVID-19 shock combined with limited ability for policy response to reverse the course of impact in the short term should continue to drive volatility, correlations and price moves.

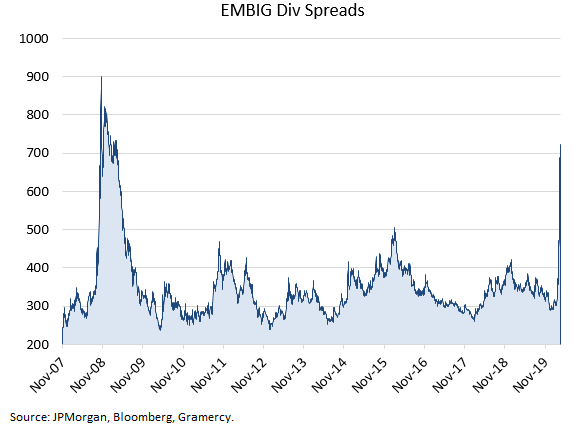

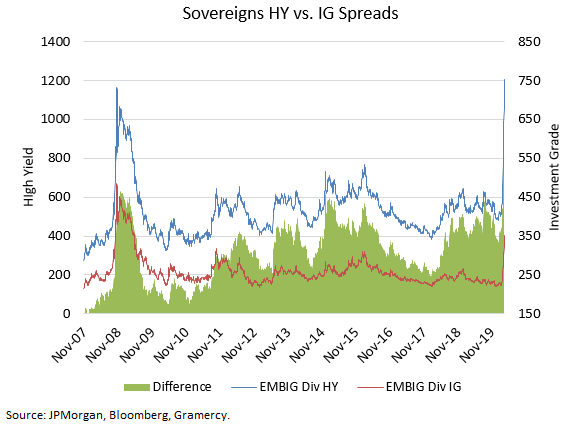

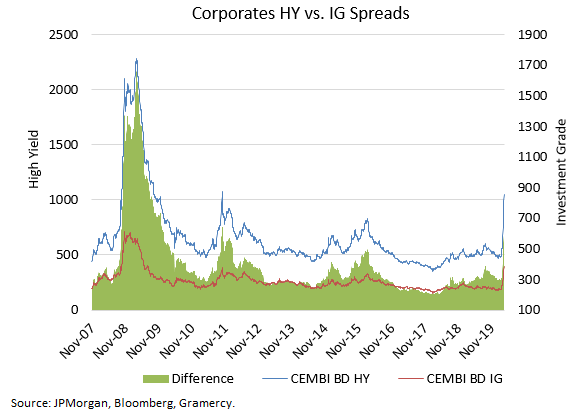

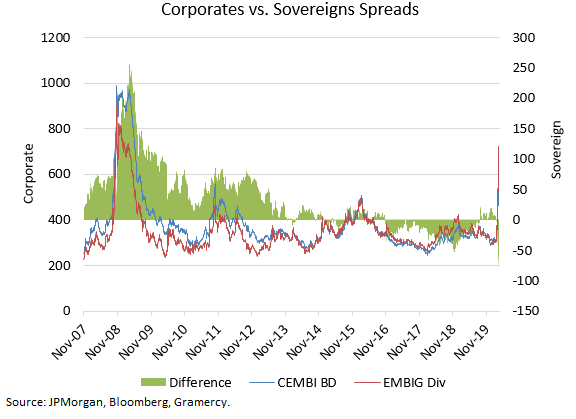

We have a preference for focused small allocations in higher quality High Yield sovereign and corporate credits in EM where fewer High Yield corporate names are oil and gas oriented relative to the U.S. index allowing for EM out-performance. We see value in the stronger and more liquid credits that are supported by some combination of reform momentum, IMF presence, constructive fiscal and external trends and, especially, ample buffers. Eventual stabilization of the coronavirus via containment and vaccine prospects coupled with a supportive policy backdrop should result in additional opportunities in EM Credit and Local Currency fixed income post dislocation (Exhibits 7a through 7d).

Exhibits 7a through 7d:

Oil market uncertainty warrants caution and careful credit selection as previously outlined. Oil prices came under heavy pressure in March due to a simultaneous supply and demand shock. Demand remains weak as the effects of the coronavirus propagate throughout the world. In addition, oil suffered a supply shock as an earlier no-deal OPEC+ meeting was followed by an increase in Saudi production to more than 12mmbpd (from 9.6mmbpd) and cuts to the Saudi OSP (Official Selling Price) of as much as $8/bbl, which created a global oil supply glut that will take some time to be absorbed by the market in the current weak demand environment. Eventually, after several consecutive days of negotiation over video conference, on April 12th the so called OPEC+ group (i.e. OPEC + Russia and Mexico) reached a deal on a historic production cut of 9.7 mb/d, significantly exceeding the previous record cut of 2.2 mb/d announced during the depths of the GFC in 2008. Despite the agreement, the immediate outlook for oil will remain constrained on the demand side by the effects of the coronavirus on global demand.

From an industry perspective, air carriers, airport operators, entertainment companies, and hotels are likely to face material headwinds. Travel bans (both official and self-imposed) will cause severe stress for air carriers in the short to medium term. Companies globally are cutting capacity and routes, as well as reducing schedules in an attempt to deal with the significant drop in demand but these measures are unlikely to suffice. The benefits of lower costs from the fall in oil prices are unlikely to offset the demand problem. Airport operators could also experience a significant negative shock to fundamentals as aeronautical revenues are usually the main source of revenue for these companies. Casinos and hotel operators are likely to see a large drop in visitors as the coronavirus spreads and governments prevent large group gatherings or potential customers start practicing self-isolation.

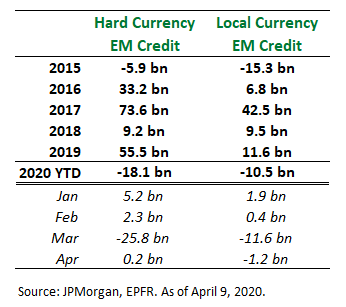

Exhibit 8: Significant Outflows from EM Year to Date

In terms of flows in and out of EM, we expect already damaged investor sentiment to continue to be further weakened by an acceleration in outflows both by dedicated and cross-over funds. We believe we have not seen the worst of the outflow story in EM yet after witnessing strong inflows since 2015. The latest EPFR release highlighted that we had outflows of $18.1 bn in EM Credit and $10.5 bn in EM Local YTD, which exceeds levels witnessed in 2015 and 2008 but are only 33% and 80% of 2019 inflows, respectively. (Exhibit 8).

The difference between now and previous, recent outflow episodes is that the market is increasingly fragile and unable to transfer risk. We see this weighing on liquidity with banks unable to adequately price size, contributing to a bearish and volatile technical scenario. The conditions which we face are a product of a selective bids and offers that are increasingly ask-driven, where pricing is mostly one-way. This is exacerbated by investor losses and a negative trading PnL, which undoubtedly leads to tighter risk budgeting and a precipitously tighter liquidity environment.

Asset Allocation within Emerging Markets

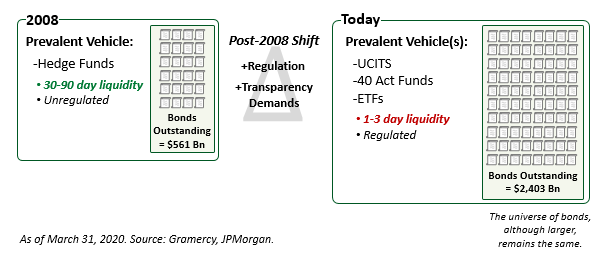

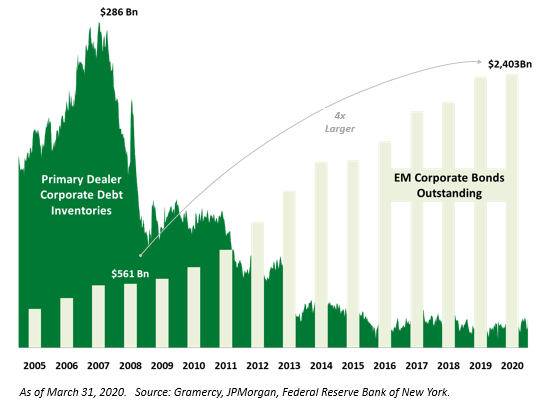

We are not surprised by the dislocations that have occurred in EM credit markets thus far, nor by the velocity or severity of these market disruptions. Last quarter, we highlighted that the perfect “dislocation storm” was brewing. This potential disturbance was characterized by massive growth of EM credit over the past decade, the promise of liquidity from vehicles (ETFs, UCITs, 40 Act Mutual funds) that can’t guarantee the underlying liquidity of their portfolios and the limited number of banks/balance sheet to provide liquidity. Over the past decade, as inflows came into the asset class, we observed inelastic supply; that is at every price there was a willing issuer of new debt/supply to soak up the demand for EM credit (Exhibits 9 and 10). However, what we have seen now (given the factors outlined above) is that when outflows came, there was not inelastic demand and as a result “liquidity” dried-up. We didn’t know what the catalyst (COVID-19) would be, but we did know the straw that would break the camel’s back would be outflows. March ushered-in record outflows to the asset class and the rapid dislocations that followed. Our Gramercy Market Monitor and other research can be found on our website.

Exhibits 9 and 10: Structural impediments to liquidity.

With the aforementioned themes and market conditions in mind, we now turn to the implications for asset allocation and security selection within emerging markets credit. As we enter the second quarter of 2020, we continue to rely upon a barbell approach to remain consistent with our dual objective of capturing the upside that has presented itself in the recent dislocation while maintaining resilience and optionality on the opportunistic approach to dynamically shifting asset allocation choices as market conditions gyrate with unparalleled volatility. However, this quarter we will change the weights of the barbell and secure their clamps to weather the extended storm on the horizon.

On one end of the barbell, we continue to look for higher-quality credit that can not only weather the bouts of continued volatility that we expect, but also provide higher quality balance sheets that will be necessary to drive proper risk-adjusted returns going forward. On the private credit front, we still prefer highly secured, structured deals. However, rather than simply funding growth, we are vetting rescue finance transactions characterized by high quality balance sheets and secured by uncorrelated assets whereby our capital can help these borrowers overcome liquidity issues as opposed to credit issues. We will continue to seek solid balance sheets and robust collateral packages in absolute terms and relative to public credit bonds.

In our EMD portfolios, as signaled, as the quarter progressed we rotated from local markets to USD sovereigns, increased the quality within High Yield or switched to High Grade corporates and accumulated a healthy cash balance. We have also actively reduced our exposure to BBB- credits with imminent and underpriced downgrade risk. This shift was driven by our desire for resiliency and the decreasing opportunity cost of de-risking the portfolios. As we enter the second quarter, we will use counter-cyclical rallies to continue increasing the credit quality in the portfolios and ensure that dislocations that we underwrite are driven by market liquidity challenges as opposed to idiosyncratic credit issues. We will focus on how different the world will be on the other side of the coronavirus crisis, which regions, countries and ultimately credits we believe will be the winners and losers, and look to position ourselves accordingly.

In our Alternative portfolios, we utilized what we believed to be cheap, asymmetric hedges (mispriced life insurance) that were available for most of the first quarter. We had not witnessed the cheapness of such hedges since 2007, both in at the money “ATM” and out of the money “OTM” hedges. As the quarter progressed, we sold the lion’s share of our ATM hedges and moved to OTM hedges in order to achieve the dual objective of protecting the portfolios against further left tail risks but also protecting against potential snap-backs similar to what we witnessed in April of 2008 when JPM “bought” Bear Stearns. As market conditions continued to deteriorate, our OTM hedges became ATM hedges and we opportunistically monetized those gains and purchased further OTM hedges. We will continue to dynamically shift the hedges from OTM to ATM and vice versa as market conditions dictate. Lastly, our Special Situations group is busy analyzing if/how to add business interruption claims related to COVID-19 to our global litigation finance strategy.

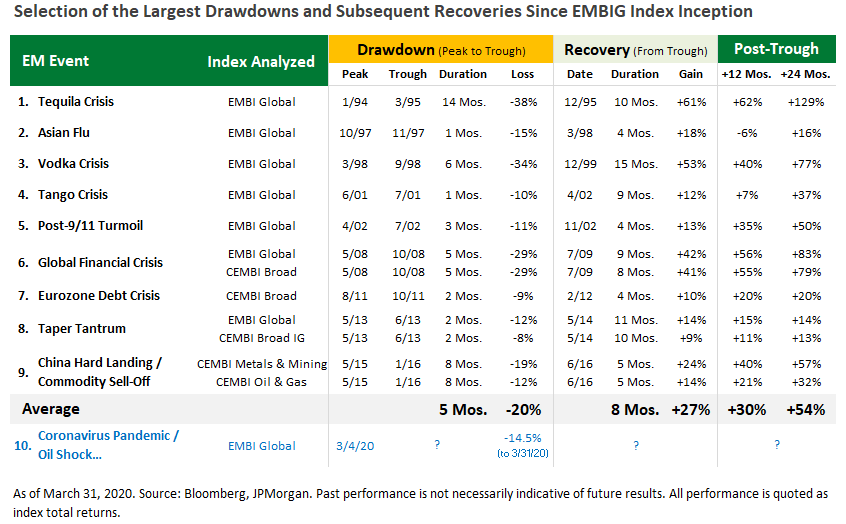

On the long side of the portfolios, we want to begin to on-board in a careful and selective fashion the dislocation that has occurred in the markets. In order to inform this disciplined approach, we refer back to the major dislocations that have occurred in EM credit of the past 25 years and will wait until the current one rivals those, yet adjusts for the uncertainties that lie ahead. Over the past 25 years we have navigated nine big systemic dislocations. They include the Tequila Crisis in 1995, the Asian Flu of 1997, Russian debt crisis 1998, GFC 2008 etc. The average drawdown from peak to trough was 20% over 5 months. For comparison sake, the current “Coronavirus Crisis” has seen markets dislocate nearly 20 percent in only one month. We highlight the investment opportunities in the rebounds back to the previous peaks: 27% in 8 months, 30% in 12 months and 54% in 24 months. (Exhibit 11). With these potential returns in contractual, USD instruments, who needs the substantially higher risk of emerging markets equity and local market debt?

Exhibit 11: Historical Drawdowns and Recoveries in Emerging Markets.

In conclusion, in our last quarterly piece we suggested that the best way for sophisticated investors to capture the extraordinary returns that would follow a dislocation was to underwrite that dislocation before it occurred. This would ensure that clients could avoid the typical paralysis that impedes one’s ability to focus on the future and not the past. Now that the dislocation is taking place, we suggest that investors look to participate in the recovery that we believe will eventually come. Of course, there are reasons to suggest that the markets may dislocate more and take longer to recover. That’s why we intend to continue to “plan the trade and trade the plan.”

About Gramercy

Gramercy is a dedicated emerging markets investment manager based in Greenwich, CT with offices in London and Buenos Aires. Our Mission is to positively impact the well-being of our clients, portfolio investments and team members. The firm, founded in 1998, seeks to provide investors with superior risk-adjusted returns through a comprehensive approach to emerging markets supported by a transparent and robust institutional platform. Gramercy offers both alternative and long-only strategies across emerging markets asset classes including capital solutions, private credit, distressed debt, USD and local currency debt, high yield/corporate debt, and special situations. Gramercy is a Registered Investment Adviser with the SEC and a Signatory of the Principles for Responsible Investment (UNPRI). Gramercy Ltd, an affiliate, is registered with the FCA.

Contact Information:

Gramercy Funds Management LLC

20 Dayton Ave

Greenwich, CT 06830

Phone: +1 203 552 1900

www.gramercy.com

Jeffrey D. Sharon, CFP, CIMA

Managing Director, Business Development

+1 203 552 1923

[email protected]

Investor Relations

[email protected]

This document is for informational purposes only, is not intended for public use or distribution and is for the sole use of the recipient. It is not intended as an offer or solicitation for the purchase or sale of any financial instruments or any investment interest in any fund or as an official confirmation of any transaction. The information contained herein, including all market prices, data and other information, are not warranted as to completeness or accuracy and are subject to change without notice at the sole and absolute discretion of Gramercy. This material is not intended to provide and should not be relied upon for accounting, tax, legal advice or investment recommendations. Certain statements made in this presentation are forward-looking and are subject to risks and uncertainties. The forward-looking statements made are based on our beliefs, assumptions and expectations of future performance, taking into account information currently available to us. Actual results could differ materially from the forward-looking statements made in this presentation. When we use the words “believe,” “expect,” “anticipate,” “plan,” “will,” “intend” or other similar expressions, we are identifying forward-looking statements. These statements are based on information available to Gramercy as of the date hereof; and Gramercy’s actual results or actions could differ materially from those stated or implied, due to risks and uncertainties associated with its business. Past performance is not necessarily indicative of future results. This presentation is strictly confidential and may not be reproduced or redistributed, in whole or in part, in any form or by any means. © 2020 Gramercy Funds Management LLC. All rights reserved.